Do you like solving riddles? How about trying to complete a puzzle with missing pieces or a puzzle with too many pieces? If your answer is yes, you might have what it takes to be a superstar insurance allocation modeler.

I recently spoke on a panel at the 35th anniversary of the ABA’s Section of Litigation Insurance Coverage Litigation Committee CLE Seminar in Tucson. The title of the panel was “Allocation – Where the Math Meets the Law, The Sequel” and the focus was on balancing the “spirit of the law” against the practical implications of modeling it. It was a “sequel” because the panel was introduced at the same conference in 2016 by a group that included my colleague, Elizabeth Hanke. You may be thinking, “Why do it again?” — and the answer is simple: there are many different factors that impact insurance allocation modeling, and new case law continues to emerge on the topic. With endless variations on how that case law interacts with policy language and interpretations of both, this panel could be resurrected every year and not be repetitive.

Allocation of long-tail claims to coverage remains a continuing area of dispute and litigation between policyholders and their insurers. Even with decades of court decisions addressing and resolving many issues, it is the math behind the implementation of these decisions that, at least in part, remains the challenge. While practitioners and courts use shorthand to describe various allocation methodologies such as “pro-rata” or “all-sums”, these basic methodologies by themselves are only the first step in actually determining the specific responsibility of any particular policy or insurer for the claims at issue. Even in cases where the courts are very specific in their language, these rulings can sometimes raise nearly as many questions as answers when applied to an entire insurance program. Fully resolving the issues and coming up with a resulting “number” requires a deep dive into the math behind the allocations and supporting legal theories.

Resolution of these coverage issues can result in a wide range of outcomes:

The goal of our panel was to offer different perspectives concerning how policyholders and insurers consider certain coverage issues as part of litigation or settlement. We focused on how various courts have resolved these coverage issues, and we used examples of allocation modeling to show the financial implications of those decisions.

The manner in — and degree to which — an occurrence-based general liability insurance program will cover a policyholder’s defense, settlement, and judgment costs for suits seeking substantial damages because of bodily injury or property damage taking place over a number of years turns on the resolution of a number of coverage issues.

Those issue often concern:

Counsel for both policyholders and insurers have a duty to their clients to consider a variety of factors very early in a dispute, and that consideration must extend beyond reviewing the guiding law and policies. These include:

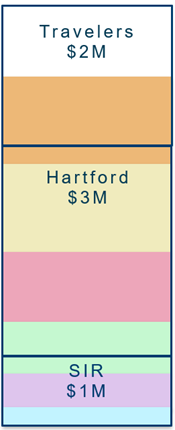

We used coverage chart graphics to explain these issues in simple terms, then discussed the complexities of these simple ideas in practice in relation to recent case law. For example, using only a single year of coverage, we showed the impact of a ruling where all losses arise out of a single occurrence versus a multiple occurrence outcome.

SINGLE YEAR OF COVERAGE

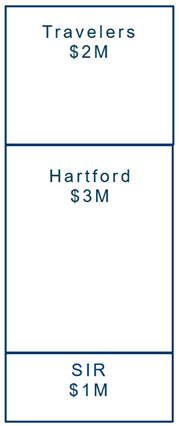

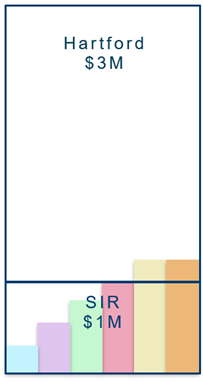

The coverage was assumed to have a $1,000,000 self-insured retention followed by an additional $5,000,000 in coverage issued by two insurers. The retention has a per occurrence limit but no aggregate limit, meaning that it must be paid in full for each separate occurrence.

THE CLAIMS

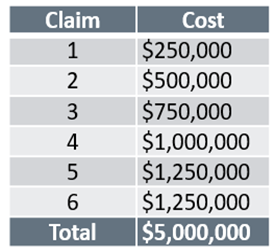

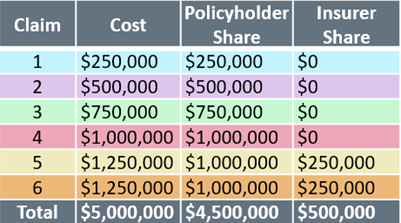

We assumed there were six claims totaling $5,000,000.

ALLOCATION

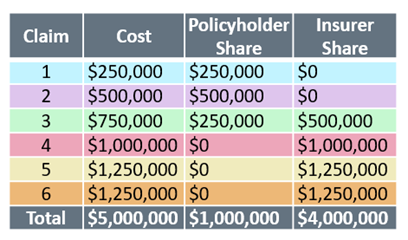

Single occurrence: Assuming a single occurrence results in a favorable outcome for the policyholder. Claims 1, 2 and a portion of claim 3 are allocated to the self-insured retention. Part of the way through claim 3, the retention has reached its limit, and the remaining claims are allocated to the insurers resulting in the policyholder collecting $4,000,000 of the $5,000,000 loss from coverage.

Multiple occurrences: Assuming each claim represents a separate occurrence results in a much less favorable outcome for the policyholder. Since the self-insured retention has a per occurrence limit and no aggregate limit, each claim is allocated to the retention first. Claims 1 through 4 have a value of $1,000,000 or less and are therefore allocated only to the retention. Claims 5 and 6 are greater than the retention’s per occurrence limit of $1,000,000 and are allocated to the retention for the first $1,000,000 and then to coverage. The result is that the policyholder collects only $500,000 of the $5,000,000 loss from coverage.

While this example is quite simple, it gets very complicated when dealing with many years and layers of coverage and when combining different combinations of interpretations of case law on different issues. Simply put, reality is messy. Sometimes an outcome that appears beneficial to an insured, such as multiple occurrences, may not be so good when modeled. Policyholders and insurers will spend considerable time negotiating, or worse, engaging in litigation to answer the question “How much does each insurer owe, if any?” The math behind the allocations is one of the most interesting aspects of practicing in the area of insurance coverage. It requires a nuanced understanding of allocation far exceeding what is spelled out in the law, and indeed excellent skills in math and puzzle solving, to advise clients on issues in these areas.

Never miss a post. Get Risky Business tips and insights delivered right to your inbox.

Managing product liabilities often means breaking complex scenarios into smaller components that can be easily understood by all parties. That’s precisely what Nancy Gutzler excels at doing.

Learn More About Nancy